Has Passive Investing Peaked?

Has Passive Investing Peaked?

Written by Warren Yeh

Head of US, Smartkarma

The first book I ever read on investing was Burton Malkiel’s “A Random Walk Down Wall Street”, originally published in 1973 and considered by many to be the Bible of passive investing. By the time I read it in the early 80’s, Professor Malkiel was Dean at the Yale School of Management and a board member of the Vanguard Funds.

It left such an impression that I put my next paycheck into the Vanguard 500 Index Fund. Shockingly, despite my bold investment, index funds (deemed “un-American” due to their defeatist “can’t beat’em join’em” attitude) remained a tiny fraction of total assets in the years that followed. In fact, by the end of 1990’s – almost 30 years later – actively managed funds still accounted for roughly 90% of funds under management.

However, since 2000, the growth of passive management (index funds and ETFs) in the US has accelerated dramatically. In particular, over the last 10 years, passive management has not only gained market share but has clearly done so at the expense of active management.

![]()

Source: “Tracking US Asset Flows”, Morningstar

Much of this growth can be attributed to ETFs with the introduction of the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY). Celebrating its 25th birthday this year, SPY is now just one of nearly 7200 ETFs worldwide according to London-based research firm ETFGI. ETFs now account for 10% of US equity ownership and 36% of daily trading volume.

As a result of these funds flows, actively managed US equity funds are now 60% of assets while passively managed funds account for nearly 40%.

ETF ($bn) | Index ($bn) | Total Passive ($bn) | Active ($bn) | Total Assets ($bn) | % Passive | |

1999 | 31.20 | 334.90 | 366.10 | 2,632.60 | 2998.70 | 12.2% |

2016 | 1,329.40 | 1,805.60 | 3,135.00 | 5,044.10 | 8,179.10 | 38.3% |

Source: Itzhak Ben-David, Francesco Franzoni, Rabih Moussawi, “Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)”. Annual Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 9, 2017

High Fees + Underperformance = Switch to Passive

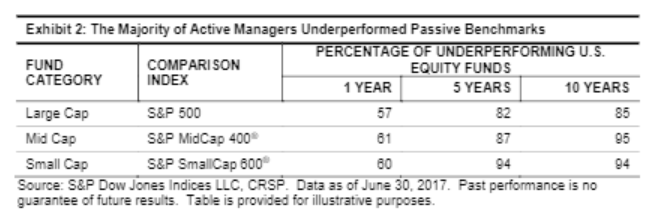

The simple reason for the move to passive investment is the combination of high fees and lousy performance. In the midst of this current bull rally, active managers have underperformed a highly resilient index. According to the recent S&P Dow Jones SPIVA Scorecard, over 80% of all active managers underperformed on a net basis over the last 10 years across almost all categories.

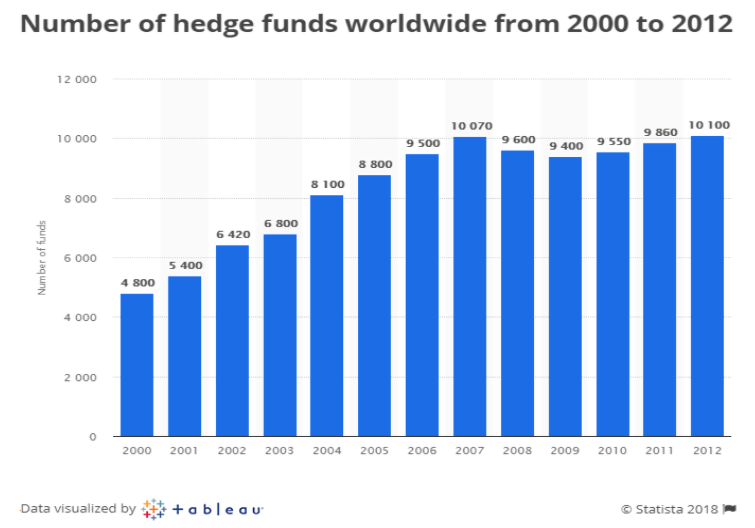

A factor that may have contributed to the underperformance of active managers was the increasingly crowded and overcompensated playing field. The proliferation of hedge funds since 2000 and massive compensation schemes attracted many players into the asset management world.

Source: Statista

I don’t think it’s a freak accident that the peaking in the number of hedge funds in 2007 coincides with the beginning of accelerated growth in passive assets.

While assets managed by hedge funds are still small relative to total actively-managed assets, the fees generated reached headline levels that often drew strong criticism and painted many active managers with the same brush. Any active manager’s underperformance became a magnified liability. Public funds had no choice but to allocate to passive strategies for far lower fee levels.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

If passive investing is a good thing, then we are now getting too much of it. Here are some of the problems.

Every stock in the particular index is treated the same way.

For every dollar that is invested in a passive fund, the tracked index members get the same pro rata allocation of that dollar (usually by market capitalization) regardless of the underlying company quality. This means that correlation among index members is high and dispersion is low. As such, the worst companies will follow the best companies in a bull market and vice versa when sentiment reverses. If these features of correlation and dispersion are maintained over extended time periods then quantitative algorithms will model this tendency as the norm further exacerbating the issue.

Some companies are found in multiple indices and thus represented across multiple ETFs. According to Bloomberg, Apple (AAPL) can be found in 198 different indices. This can range from 1.3% of the Bloomberg World Index to 69% of the NASDAQ US Large Cap Growth Index. As money pours into a variety of ETFs for a variety of different reasons, AAPL shares will be bought across many different categories. Is it a surprise then that AAPL’s largest owners are Vanguard, Blackrock, and State Street? After all these three institutions account for 83% of the US ETF market and 70% globally. Look across any S&P 500 stock and three of the top five owners will be index funds.

Passive funds own a lot of stock but do not vote actively.

Proxy voting data from 2016 show that index funds vote with management 97% of the time. That shouldn’t be surprising. Low fees at these funds do not typically support an active proxy war. But it also means that issues like executive compensation, stock buybacks, and other practices condoned by boards may go unchecked, especially if boards recognize that the majority of shareholders are passive.

ETFs can exacerbate market volatility.

On May 6, 2010, bad news surrounding Greek debt resulted in an equity market sell-off. That’s understandable, but the S&P 500 dropped 9% in 20 minutes. How does this happen?

The majority of ETFs are open-ended. This means that when the ETF price rises above the NAV of its basket of index components then market makers (called “Authorized Participants” or APs) will sell newly-created ETF shares and buy index constituents. But when the index components sell-off and ETF owners dump their ETFs, then APs are supposed to buy the ETFs and sell the components. In situations where liquidity for the index components dries up (ie bids fall away), APs have been reluctant to perform this arbitrage function. The downward spiral quickly becomes self-fulfilling.

The Flash Crash of 2010 resulted in circuit breakers being applied to slow down these death spirals. But that seemed to have backfired on Aug 24, 2015 when 327 ETFs were halted due to limit down restrictions and 11 ETFs were halted 10 or more times. Again, APs were inactive when pricing clarity was limited.

It would be unfair to pin all the blame on APs for ETF dysfunction. Many of the most volatile ETFs are leveraged synthetic ETFs designed to provide multiples of daily index percentage rises and falls. Instead of buying the physical assets to replicate the index, synthetics enter into swap agreements with a counter-party (which many times may be an affiliated entity) basically guaranteeing the index return. How that counter-party offsets the liability is fairly irrelevant to the end user of an ETF. But during periods of extreme volatility, counter-party risk can create a domino effect that’s unanticipated. I don’t know about you but I still get a little nervous whenever I see the words “counter-party” and “leverage” in the same paragraph.

Conclusion

Flash crashes are just one symptom or warning sign of a situation that has spiraled a bit too far. As indexing grows it becomes more self-fulfilling. Unlike other market phenomena, there is no self-correcting mechanism. In my opinion, we are reaching a tipping point where active managers are becoming more important than ever. Fees have been negotiated down, many funds have closed and passive continues to snowball (US ETFs in January attracted $68.1 bn the most ever in a single month). But until the remaining managers show some outperformance, the default mechanism will continue to move toward passive. Ironically most active managers I have interviewed feel that this outperformance can only come when the market sells off. Assuming the sell off unwinds the overowned index names, active managers need to be invested in those less-followed, un-indexed, and ignored ideas or else they get swept down the same drain. Unconflicted independent research that examines these less-followed ideas will be critical in surviving the next market decline. And those active managers who want to outperform during that period need to be investing in those ideas now in order to be the winners going forward.

Has Passive Investing Peaked?

Has Passive Investing Peaked?

Written by Warren Yeh

Head of US, Smartkarma

Has Passive Investing Peaked?

Has Passive Investing Peaked?