How Does Liquidity Affect Asset Markets?

by Michael J. Howell

Managing Director, Crossborder Capital

Read more of Michael’s work on Smartkarma!

Explaining the CrossBorder Capital Liquidity (Flow of Funds) Model

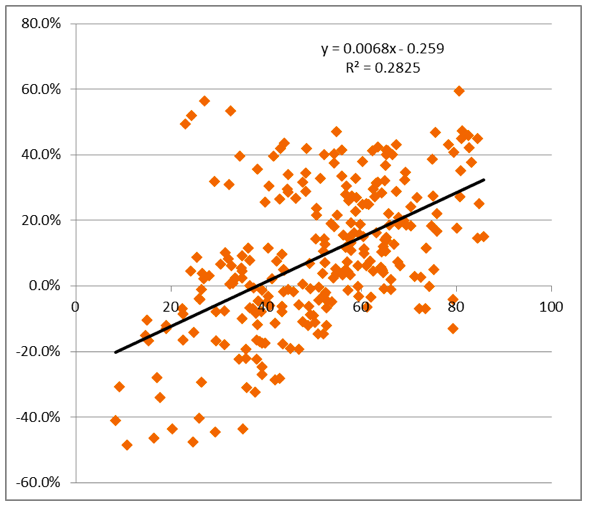

The recent injection of nearly US$10 trillion of Central Bank ‘quantitative easing’ evidences the importance of liquidity to investment valuations, such as bond yields, stock markets and house prices. In short, money moves markets. But it is not just the actions of the grey suits at the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank that matter. Savings flows, bank credit, corporate cash flow, cross-border capital inflows and the vast pool of Chinese money also count. In fact, their contributions to Global Liquidity are often now bigger and faster-moving. These swings in Global Liquidity drive asset markets up and down. Peaks in the Global Liquidity cycle typically precede similar asset market peaks, while lows in the Global Liquidity cycle warn of upcoming banking problems and possible economic recession. The chart below shows the relationship between Emerging Market equities and the CrossBorder Capital liquidity data in index form.

Emerging Market Stocks: Deviations of Returns from Trend (LHS) and Liquidity (Index), 1996-2017

It seems clear that as the World market gets bigger in size it becomes more volatile since banking/ credit crises now hit with an apparent regularity every 8-10 years, such as in 1996, 1974, 1982, 1990, 1997/98, 2007/08. The Y2K technology bubble appears to break this pattern, but still proves the rule because it was pumped up by Central Bank cash. With many policy-makers again debating how much to reduce their recent money creation, another inflection may be now due with typical far-reaching effects? The pool of Global Liquidity total some US$115 trillion, or roughly 50% bigger than World GDP. China (US$30 trillion) and the US (US$28 trillion) dominate the data, with China’s People’s Bank now the largest Central Bank in the World by balance sheet size. Global Liquidity and, notably, credit typically lead to the build-up of financial system vulnerabilities through heightened asset price inflation, leverage and maturity or funding mismatches. Thus, cross-border capital flows frequently provide the marginal source of financing in the run-up to financial crises. Over the last three years alone some US$3 trillion of liquidity has switched back-and-forth between the US, China and the Eurozone. This rollercoaster heightens currency market volatility, which then often spreads into share prices.

But is the impact of liquidity really understood? The circular flow of money is a popular starting point for macroeconomics. Nonetheless, the standard modern textbook introduction using the income-expenditure model is woefully incomplete. It overlooks the fact that economic agents can spend more or less than their incomes because of flows between the real economy and the asset economy. In practice, the interaction between incomes and expenditures are NOT circular at all because these flows of real economy payments are being continuously disturbed by larger flows into and out of the asset economy, and the latter’s dominance means that in practice they can result in large changes in real economy expenditures that are unrelated to either current or past incomes. Because these flows between the real and asset economies are likely to be large when asset prices differ sizeably from their equilibrium levels, asset price valuation is critical to the macroeconomic outlook. The future level of asset prices and hence the value of national wealth, like GDP, are themselves in large part functions of the quantity of money and credit. And, because the financial system can itself create credit, it is central to the determination of macroeconomic outcomes. But strangely the financial system is often ignored in the traditional textbook narratives.

Conventional textbook chapters on ‘Money and Banking’ typically focus on the so-called deposit multiplier. But, again, the World doesn’t work like this. First, money supply can no longer be measured by the retail deposit liabilities of high street banks (e.g. M2). Second, credit, not deposits are what really matter. This model assumes that banks are constrained by the supply of reserve assets and not funding constrained. Yet every liquidity crisis we can think of, and notably 2008, represents a funding problem. In this sense, Central Banks are one among many sources of funding, albeit sometimes an important source. However, the dominance of Western Central Banks is being eclipsed, not just be the availability of often vast off-shore funding pools, such as the Eurodollar Markets, but also by newly emerging authorities, such as the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). Investors should be looking more-and-more at the PBoC and not least because in size it is already one fifth bigger than the US Federal Reserve.

Liquidity operates through two main conduits: (1) the exchange rate and (2) changes to bond and equity risk premia. The drivers consist of both the quantity and also the quality, i.e. different types, of liquidity flows. Specifically, we have found that Central Bank liquidity (now popularly dubbed ‘QE’) impacts the interest rate term structure both directly by pushing down short-term rates and indirectly by raising term premia, particularly at longer investment horizons. In short, the yield curve steepens and by association, lending becomes more profitable as bank margins widen alongside. All this follows because government bonds are held as ‘safe assets’ by many investors. Increases and decreases in perceived systemic risk result in investors demanding either more or fewer ‘safe assets’, and in the process lowering and raising term premia. This, in turn, forces the interest rate yield curve to steepen or flatten, respectively, as investors extend and reduce their investment time horizons. A steeper (flatter) yield curve leads to more (less) duration risk. Because Central Bank liquidity also represents the supply of domestic currency, it follows that more (less) quantitative easing usually leads to a weaker (stronger) nominal exchange rate.

The private sector also a part in exchange rate adjustment. Private sector liquidity measures the cash flow generation (i.e. both new credit and savings) of the domestic private sector, including households, corporations and financial institutions. Greater (less) cash flow generation leads to a rising (falling) real exchange rate. The real exchange rate is here defined as the nominal exchange rate adjusted for some price index, such as consumer prices, but which also includes asset prices. Monetary transmission involves some combination of exchange rate and general price adjustment. In fact, the stronger is private sector liquidity and the tighter Central Bank liquidity, the more that the nominal exchange rate will adjust upwards. In contrast, when strong private sector liquidity is matched by equally strong Central Bank liquidity, the nominal exchange rate will remain roughly constant, with the bulk of the adjustment falling on to prices, and (given that consumer prices tend to be ‘sticky’), in practice, this effectively means higher asset prices.

We find that cross-border flows of foreign liquidity act differently according to whether they affect Developed or Emerging Markets. Large net inflows into Developed Markets (i.e. capital shifts back in to the ‘core’ economies) tend to be associated with lower investor ‘risk appetite’ and the greater demand for ‘safe assets’ such as G7 government bonds. Yet, larger inflows into Emerging Markets (i.e. capital shifts from ‘core’ to ‘periphery’) tend to be associated with increasing ‘risk appetite’ and a bigger demand by foreign investors for Emerging Market risk assets.

How do we use these indicators to invest? In practice, we first select from among markets with strong private sector liquidity, those where the prevailing investor risk appetite is low. Next, we assess Central Bank liquidity. High Central Bank liquidity reinforces our conviction about owning domestic risk assets as opposed to bonds, but warns about possible exchange rate weakness. If the economy is an Emerging Market, then strong cross-border inflows add further to our risk asset conviction. In the Developed Market case, it warns against being too downbeat on the currency and government bonds.

Read more of Michael’s work on Smartkarma!